A Comprehensive History of Corbin Park

Larger than most New Hampshire towns and stocked with exotic animals, this enormous "Millionaires' Hunt Club" remains shrouded in secrecy. (1 hour read)

Image Description: A black & white photograph of a large American bison, standing on a wintry hillside, eyes closed. The bison has two curved horns and a dark, lustrous coat. The caption reads: The King of the Corbin Herd. End of description.

A Comprehensive History of Corbin Park

by August Longpré

We are deep in the woods and newly fallen snow crunches as it compacts beneath my snowshoes. Ahead of me goes my friend and ahead of both of us have gone a pair of coyotes whose tracks lead us most of the way to our destination. Our goal is to steal a glance into Corbin Park, the largest private hunting preserve this side of The Mississippi.1 We trek through dormant logging operations, cross streams, tiptoe along the edge of a frozen pond that abuts the park’s forbidding fence, and lastly, scramble up a steep bluff to arrive at the spot we observed from satellite imagery.

Our view from the small clearing atop the hill is spellbinding. From this elevated vantage point we can see into the park more clearly than ever before. Sprawling before us, stands of mature red spruce sway back and forth in a steady wind, their tops caked in white. Behind them, the peaks of Croydon and Grantham mountains loom in faded contrast against a gray backdrop alive with driven snow. Despite having calculated distances and angles, we are unable to get an unobstructed view of the feeding station where packs of wild boar come to eat. Our sightline is impeded by a stand of evergreens which I suspect is intentional.

I grew up on the other side of the hill—outside the fence—unable to develop relationships with my home’s two tallest peaks because of their confinement within the park. The scenery here is deeply familiar yet these woods feel a world apart. The air reeks of contradictions; fenced wilderness, discreet grandeur, conspicuous secrecy. History is so palpable here, but we are excluded from it. We make the long walk back to the trailhead with a renewed commitment that this story be understood by those who care to investigate it.

Corbin Park is an enormous private hunting preserve, one of the largest in the United States. It is enclosed by 36 miles of fence topped with barbed wire making it larger than 60% of towns in the state.2 The park was founded in 1890 by Austin Corbin, a robber baron from Newport, NH who amassed his fortune through underhanded and deceitful business tactics.3 He stocked the park with around twenty exotic animal species for the purposes of hunting. Today, it is owned by a clandestine group of roughly 30 “sportsmen” who pay annual membership fees rumored to be in the tens of thousands of dollars.4 They come to hunt the animals that Corbin sequestered within his compound. Despite its size however, few locals know the sordid details of its formation or how it operates today.

Image Description: A satellite image of part of the “Upper Valley”. Highlighted are interstates 89 and 91, as well as the names of the towns in the area. A red line outlines the boundaries of Corbin Park in the bottom right of the image. The two interstates intersect near Lebanon, New Hampshire. The map shows towns as far north as Norwich, Vermont, as far west as Reading, Vermont, as far south as Weathersfield, Vermont, and as far east as Enfield, New Hampshire. Corbin Park stands out as a massive tract of land in the southeast quadrant, just across the Connecticut River from Kaskadenak (or Mount Ascutney). End of description.

Unfortunately, much of the written history inaccurately portrays Austin Corbin as a benevolent, “self-made millionaire”. Occasionally, authors make vague reference to his unsavory business tactics but decline to go into detail. Few authors (nowadays at least) have critically examined how Corbin garnered his wealth, or the ecological implications of his creation, which has since been passed into the hands of 30 faceless businessmen. This essay intends to provide a comprehensive history of Corbin Park, its founder, and its current caretakers. I contextualize events in the park’s history by placing them within a larger natural history of the region. I recount these histories by compiling existing texts, synthesizing them into a cohesive story, and viewing them through a critical lens. I have included citations so that my steps can be retraced.

Before delving into this land based history, it is necessary to underscore that Corbin Park is located on the unceded lands of the Abenaki peoples. When he fenced his property, Austin Corbin imposed on the land an impassable barrier, one that exemplifies a key tenant of settler-land relationships; he believed that he owned the land. He believed that all of the animals and trees and ponds and mountains were his to hoard, and in turn, his from which to exclude others.5 He and those of his ilk are sadly mistaken.

In order to understand the park, we must understand the man who created it. Austin Corbin was born in Newport, New Hampshire in 1827. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1849 and started to work for Ralph Metcalf, who eventually became governor of New Hampshire. In 1851, Corbin headed west with Metcalf’s political and business connections in tow, as well as a cache of investor money. Metcalf alone loaned him $1,200, an enormous sum at the time. Corbin took the money to Davenport, Iowa where he started as a lawyer but soon joined a banking firm, quickly rising to the position of partner. He entered into the lucrative business of real estate where his specialties were purchasing tax liens on properties and selling mortgages to the droves of settlers that moved west.67

Corbin’s bank was one of the few that avoided shutdown during the Panic of 1857. Banking at the time was generally an unstable affair. In 1863, Congress passed the National Banking and Currency Act and awarded Austin Corbin and his associates the first charter for the First National Bank of Davenport. According to the bank’s published history, it was the first national bank in the country under the new rules. Although there is no strong record of their business relationship, it no doubt worked to Corbin’s favor that the author of the National Banking and Currency Act was in fact his cousin, Salmon P. Chase, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury from nearby Cornish, New Hampshire.8

Having been first in line when the government moved to stabilize the banking industry, Corbin’s bank generated enormous profits. Corbin served as bank president for two years and in that time, the bank’s assets increased fivefold. With his now sizable fortune, Corbin decided to return to the east coast. He relocated to Manhattan Island where he could reap further profits by connecting capital in the east with farmers in the west. Congress did not allow for commercial banks to hold mortgages, but his firm, the Corbin Banking Company, circumvented this rule by working with mortgage companies and a network of brokers to sell mortgages to farmers out west. Those mortgages would have been profitable enough but Corbin’s schemes extracted even more wealth. His practices were illegal and he was convicted of usury, but he successfully swindled enough farmers to make himself a millionaire.9

Corbin generated huge returns for his financial backers and faced little to no consequences. Later in life, an article in The Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine would describe him as belonging to “that tribe of human monsters who prey upon [the poor], who combine the natures of hog and shark [and], being influenced by greed, make war upon the weak.”10 The article, which was written by Eugene Debs, also described Corbin as a “land pirate” and “the Napoleon of Knavery.”11

Image Description: A black & white photograph of Austin Corbin. He is dressed in a black suit jacket with a white undershirt and black bowtie. His head is bald and he has a beard that juts out from his chin and wraps around his jaw. His face is stern and his gaze purposeful. The shadows on the side of his face make him appear slightly ominous. End of description.

Soon after arriving in Manhattan, he took an interest in Long Island. One nearly ubiquitous story is that when doctors recommended that Corbin’s sickly child be exposed to ocean air, he took his family to visit what is now Coney Island. While there, he gazed out on the beach and hatched his plan for development. This was likely a work of utter fiction contrived by journalist William H. Stillwell, who penned similarly dubious tales for other local businessmen in exchange for kickbacks.12 However the idea came to him, Corbin intended to build an extravagant seaside resort at Manhattan Beach in the town of Gravesend. He hired Gravesend’s corrupt surveyor and had him acquire parcels by any means necessary. Some he purchased, and others he simply surveyed out of existence. Once he had control of Manhattan Beach, Corbin financed construction of the Manhattan Beach Hotel, which opened in 1877. The hotel was grand and luxurious and President Ulysses S. Grant helped cut the ribbon at its opening. Corbin also opened a new railway system to transport beachgoers to and from the city. He hired Pinkerton guards to patrol the area and keep out undesirables.13

Corbin cared little for his guests or employees, as was demonstrated by a calamitous night in April of 1880. After a concert at his Manhattan Beach Hotel, thousands of patrons poured into the hotel’s dining room, which Corbin intentionally understaffed so as to induce guests to stay the night rather than take his train back to the city. Hungry patrons stood in line for hours and people hurled abuse at the frantic waitstaff who were careening around corners at full tilt. The majority of those waiting to eat never got the chance because at 9pm, the bell rang for the final train back to the city. Pandemonium ensued. Patrons who had already eaten but were yet to pay their waiters took off for the train. Many who had not eaten threw any residual decorum to the side and grabbed food with their bare hands before running for the door. Waiters became frantic because they had not received any tips. Later that evening, groups set off down the beach to catch the 11pm train at West Brighton but the station was closed and they injured themselves trying to navigate the darkness.14

Not long after the hotel’s opening, Corbin sought to bar all Jewish patrons from entry. He stated clearly: “We do not like the Jews as a class”. Corbin was himself a founding member of the short-lived American Society for the Suppression of Jews. His bigotry persisted throughout his life. Years later he would also bar a Chinese passenger from entering the cabin on one of his ferries. The New York Commercial Advertizer wrote that if Corbin wished to purge his hotel of impurities, he might start by excluding his elderly Wall Street friends who checked in with their young chorus girls.15

William H. Stillwell, the aforementioned journalist in Corbin’s pocket, ended up working for one of Corbin’s companies and even introduced him to Gravesend’s Supervisor, John Mckane.16 Corbin colluded with Mckane to steal the land needed to build his second massive luxury hotel: The Oriental. Quietly, Mckane sold Corbin land that was held in common by the town. Corbin bought 500 acres of bayfront and beachfront property for $1,500, or $3 an acre. Word got out that Corbin had acquired the land for approximately one one-hundredth of its value and Gravesend patentees called a protest meeting to nullify the sale. On the night of the meeting, Corbin and Mckane packed the town hall with their goons and prevented opponents from entering the building. After a vote in their favor, the sale went through. The Oriental hotel opened in 1880, this time with President Rutherford B. Hayes as guest of honor.17 Corbin had not done the necessary site analysis and his hotels were routinely damaged by the unpredictable and destructive forces of the ocean.18

Image Description: A black & white panoramic rendering of Corbin’s seaside developments at Manhattan Beach. From left to right are the Marine Railway Station, the Manhattan Beach Hotel, the Bathing Pavillion, the Restaurant, and the Oriental Hotel. The two hotels look like castles. The beach in front of the buildings is crowded with hotel guests and the ocean laps at the shore. One can imagine a storm surge effortlessly destroying aspects of Corbin’s properties. End of description.

Corbin understood that in the late 1800s, railroads were his ticket to the upper echelons of society. His peer, J. P. Morgan, who would later visit Corbin’s park to hunt, formed a trust to control the struggling Reading Railroad. He named Corbin as president. In virtually his first act as president, Corbin hired strikebreakers, undermining the existing labor force and setting the tone for how he would conduct business in his new rail ventures. His objective was to expand his wealth and, to that end, Corbin manipulated the industry for his own gain. When his Reading line could not complete lease payments to the New Jersey line, Corbin invested heavily in the New Jersey to benefit his personal finances.19 In 1881, he gained control of the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) which, according to contemporary views, was bankrupt and had been neglected. He consolidated the LIRR with other lines and invested in improved infrastructure. An article in the Brooklyn Union-Argus stated, "Mr. Corbin's plans for the development of Long Island are so comprehensive that practical people [...] may be inclined to consider them as merely imaginative. But Mr. Corbin is backed by almost limitless foreign capital".20 In the history of the LIRR, no other president commanded the immense wealth and political influence with which Corbin built his empire. He turned the LIRR into a profitable enterprise and set the stage for development of Long Island in the 19th century. Many viewed him with derision because he routinely swindled people for his own profit. His exploits earned him the sarcastic title of “King of Long Island”.21

Corbin’s greed was not limited to east and west, he also had lucrative dealings in the south. One of his revenue streams was from an Arkansas property, Sunnyside Plantation, which he acquired in 1886 as repayment of debt incurred by John Calhoun II, grandson of the former president.22 Calhoun and his brother were regarded as prominent financiers at the time. Corbin bought up and consolidated several surrounding plantations under the auspices of the Sunnyside Company.23 He financed construction of a mansion there, which he creatively named Corbin House and moored his boat, Austin Corbin, on Lake Chicot.24 He installed a railroad from the cotton fields to the gin. The Calhoun brothers had been attempting to lure formerly enslaved African Americans into returning to work on their old plantations, but Corbin had little success with this approach. Many freed slaves were distrustful of him.25 In 1894, he found the exploitable labor force he was looking for in the form of prison inmates. Corbin entered into an agreement with the State of Arkansas in which he could lease prisoners to work his fields. He was given 250 convicts to pick cotton on his plantation, with profits shared between him and the state. This arrangement differed little from the institution of slavery that had preceded it. Later, the deal would include a sharecropping provision, which further insulated him from the risks associated with commercial agriculture.26

Corbin bumped shoulders with the most powerful people in the world. With his eyes on even more money, he struck a deal with the Mayor of Rome. Prince Emanuele Ruspoli would recruit impoverished Italian peasants and send them to Corbin’s Sunnyside Plantation. Corbin’s goal was to redirect Italian immigration away from New York and toward the center of the country. He arranged for the immigration of 100 families annually for five consecutive years. Ruspoli rounded them up and Corbin charged them inflated prices for everything from boat passage to the tools they would need to work his land. The first wave of over 500 Italian Catholics arrived at Sunnyside in December of 1895.27 We will revisit them later in the essay.

Perhaps the most infamous example of Corbin’s dastardly business tactics was the land theft of the Montaukett people of Long Island. He ambitiously sought to open a port at Montauk point on the easternmost tip of the island. Corbin hoped that transatlantic passengers and cargo would arrive at his port and use his railroad to reach New York City a full day faster than they could on a ship28. The port would shorten transatlantic voyages by 120 miles and ships could avoid the crowded harbor at New York. Corbin and his business associate Arthur Benson devised a scheme to develop the island, which involved excavating Fort Pond Bay to make room for an international shipping terminal. Benson was to buy the land and sell it to Corbin’s railroad. Then he and Corbin could build resorts and housing made accessible by the LIRR.29 The plan seemed to all but guarantee outrageous profits. The only problem was that a group of Montaukett people were living on a 1,200 acre tract of land called Indian Fields, directly in the middle of the desired area. The Montauketts had previously resided on the island for thousands of years.30 At the time, they were living under the terms of an East Hampton Town lease which granted them residency among other rights “in perpetuity”.31

Benson sought clear ownership of Montauk point. Since he did not want an impoverished indigenous community living within his money-making real estate venture, he would have to convince (or induce) the Montauketts to cede their rights and leave their land. There appears to be no evidence indicating that the Montauketts were ever approached as a group. Instead, Benson hired town assessor Nathaniel Dominy to approach individuals and persuade them to move to “comfortable homes” and land that Benson would provide in the Freetown section of East Hampton. Dominy offered some Montauketts as little as $10 to sign away their rights. He told them that they could return to Indian Fields whenever they wanted, a promise he would later admit was a lie. Benson’s promises were empty. A Montaukett native named Nathan Cuffee testified that “most of the houses, except one, are built of plain pine boards, stood on end, without any chimneys to them, without any plastering; just such a pen as I would build for a pig.” Another Montaukett person named Eugene Johnson said that when his people tried to return to Indian Fields, they were arrested or removed “by force”.32 Corbin had hired guards to close Montauk off to communal uses.33 Their ancestral lands had effectively been stolen from them and they found themselves barred from returning. A Montaukett person named Robert Pharaoh described the land transfer as “coercion, a land fraud—leading people with promises that never happened.” He continued, “These were people with very little money, who worked as domestics and were victimized from the time they lost their lands until they passed away.”34

Despite lack of legal ownership, and facing formidable opposition, the Montauketts were able to delay the physical development of Montauk Point through repeated lawsuits. By 1890, the land there was worth somewhere between $3 million and $4 million. Benson recouped a large part of his investment by selling huge tracts of land to Corbin’s railroad. Corbin had invested in the project both as president of the LIRR and as a private individual.35 With control of the railroad, he could manipulate it to impress his guests. He routinely entertained powerful people at his home in Babylon, NY. When visited there by President Chester A. Arthur, Corbin cleared rail traffic so the president could make the 37 mile journey back to Long Island City in just 40 minutes.36 At his Babylon estate, Corbin kept deer, elk, and antelope but the animals soon outgrew that space.

Beginning in late 1889, Corbin embarked on the project for which many of us know him: his park. He set about buying land surrounding his family’s home in Newport, New Hampshire. He demolished the entire building except for his childhood bedroom, around which he built his new mansion. He hired a young farmer named Sydney Stockwell and tasked him with purchasing properties in the area. Over a three year period, Stockwell acquired between 275 and 373 properties, including 63 farms with buildings and land totaling well over 20,000 acres.37

Many of these farms had been abandoned during the mass westward exodus of New England settlers, spurred by a confluence of factors including the ecological degradation inherent to their farming practices, influences within a capitalist market, a sense of manifest destiny, and the fact they did not practice primogeniture.38

In 1890, Corbin hired men to fence off his land.39 Some people were reluctant to sell. They didn’t capitulate until after Corbin landlocked their properties and persuaded the towns to stop maintaining their roads. Reuben Ellis, a resident of Croydon, sued Corbin for restricting access to his holdings. Ellis had been furnished a pass to move through the park “provided he will pay the expense of a gatekeeper”. The case reached the NH Supreme Court, which sided with Ellis. He finally sold in 1906 with a provision to cut lumber for a specified number of years.40

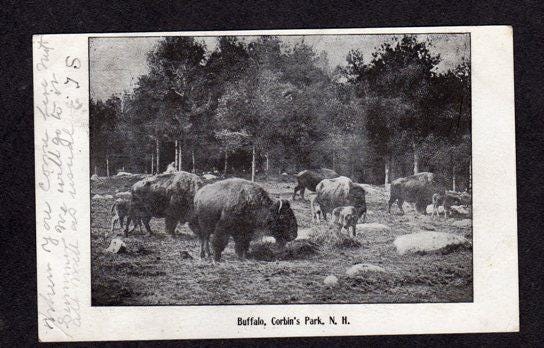

Image Description: A map of Corbin Park and the surrounding area. Labeled are the towns of Claremont, Newport, Croydon, Cornish, Grantham, and Plainfield, New Hampshire. With its boundaries highlighted in green, Corbin Park comprises a small part of Newport, two significant chunks of Cornish, an enormous part of Croydon, a big piece of Plainfield, and a comparably large piece of Grantham. End of description.

Corbin’s park consists of roughly 26,000 acres41 and spans five New Hampshire towns; Newport, Plainfield, Cornish, Grantham, and Croydon. Of these five, the largest section is in Croydon totaling over 10,000 acres. Confined within the fence are two large mountains—Grantham Mountain and Croydon Peak—three sizable ponds, and many miles of streams. Aside from a few meadows and the very top of Grantham Mountain, the land there is covered in trees. The fence itself is 36 miles long and measures 12 feet high in most places. It extends underground three feet in an attempt to keep boar from digging out. When it went up, it enclosed 15 miles of roads within the park. Corbin added 15 more miles of roads with granite watering troughs every four miles. There were also orchards, vineyards, sawmills, machinery, farmhouses with abandoned buildings, two schools, and a cemetery. Some of these buildings were modified into hunting accommodations, but most were left to deteriorate. Empty foundations are all that is left of them.42

The majority of settlers who had inhabited these now abandoned areas were descended from English colonists. They came up the Connecticut River valley following the English defeat of the French at Montreal in 1759. They received charters from their English King and moved into lands that had been stewarded by the Abenaki for thousands of years and hundreds of generations. In their brief residency, the settlers deforested the land and overgrazed their hillside pastures. Then, many of them were gone; headed west to wreak further havoc. Their innumerable stonewalls—remnants of the overzealous wool industry—still crisscross our woods today.4344

A local observer commented on Corbin’s land grabs by inventing a rhyme: “Austin Corbin, grasping soul, wants this land from pole to pole. Croydon people, bless your stars, you'll find plenty of land on Mars.”45

Despite perceptions of Corbin, some landowners received what they believed to be fair payment. A local man named Fred Barton was quoted as saying, “I sold my homestead farm of 900 acres, with good buildings, for $2800. I was perfectly satisfied with the price and [...] I am much better off financially than I was before.” Fortunately for Barton, he already had property to move to in Lempster. His experience with Corbin differed drastically from that of the Montauketts, or the convict laborers, or his Jewish and Chinese patrons, or the poor Italian peasants, or the countless other farmers that he took advantage of. The land within Corbin park was acquired for roughly $5 an acre.46

Corbin formed the park under a non-profit organization called the Blue Mountain Forest Association, named for the mountain’s blue spruce. Native animals already within the park included but were not limited to snowshoe hare, ruffed grouse, wood duck, mink, fisher, otter, raccoon, skunk, and trout. The White-tailed Deer, black bear, wolf, and panther had been extirpated from the region for several generations before the park was built.47 In addition to the animals already within the park, Corbin stocked it for hunting by shipping in animals from disparate parts of the world. Naturally, they arrived by train.

Image Description: A black & white photograph of a lone bison being transported in a large cage atop a wagon. The wagon has wheels with long wooden spokes and is pulled by two horses. A figure sits at the reins and another looks on from a distance. The bison is traveling from the train station to a new home in Corbin’s park. End of description.

Over the span of a few years, he arranged for the capture and trafficking of around twenty species including eurasian boar from Germany and Russia, wapiti, or elk, from Minnesota, American bison from the plains, moose from Canada, pronghorn antelope, caribou, reindeer from Labrador, rabbits, Chinese pheasants, bobwhite quail, beavers, squirrels, bighorn sheep, Himalayan mountain goats, and several species of deer.484950 When the first shipment of white-tailed deer arrived by rail, the entire town of Newport turned out to see a live deer in the flesh. Deer had been gone from the region for more than a generation due to habitat destruction and overhunting. Corbin’s intentions were to create a preserve where he could hunt animals and occasionally sell them to buyers across the country. He wanted the park to be a place for “all the animals of the world that can live there harmoniously” though he specified, “no bears, panthers, foxes, or wolves.” He was determined to be the top predator in his expensively curated wilderness. He hired rangers who traveled about the grounds on horseback. Hunters employed English foxhounds, bloodhounds, French boarhounds, and Great Danes to do the dirty work of hunting prey trapped within the park.51

Image Description: A black & white photograph of seven white men, three dogs, and two dead boar which the men have strung up and are now posing with. The two boar are massive, much larger than the dogs and would surely overpower any of the men on their own. From left to right the names read: Ralph Woodward, Abe Read, Allen Jenson, Palmer Read, John Meyette, Ralph Jordan, and Clarence King. End of description.

The vast majority of animals that he imported were dead within the first year. They were not suited to the climate or the conditions.52 Some populations were able to gain a foothold; most notably, and unsurprisingly, white-tailed deer, beaver, elk, and wild boar. The bison also survived. Corbin had hired a man by the name of Billy Morrison from Scotland to look after them. In the beginning, the boar were hunted on horseback with javelins and Austrian boarsetter dogs.53 By 1893, Corbin decided he wanted to get rid of the boar and instituted some hunting excursions with that end in view.54 These attempts were wholly inadequate because boar are wily and they reproduce frequently, doing so in large litters. Populations exceeded the available food supply and feed sites were furnished to keep animals alive through winter.55

Nonetheless, Corbin’s Park was a popular destination for Corbin’s powerful friends such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and J. P. Morgan, who would come up for a day or two of shooting in the countryside.56 Corbin financed construction of the Northville rail station to facilitate his private rail travel to and from the city. He also entertained well-known local artists Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Maxfield Parrish. From New York, Corbin would send up his “colored cook”, Daniel Webster, a few days in advance to prepare for parties at the estate.57

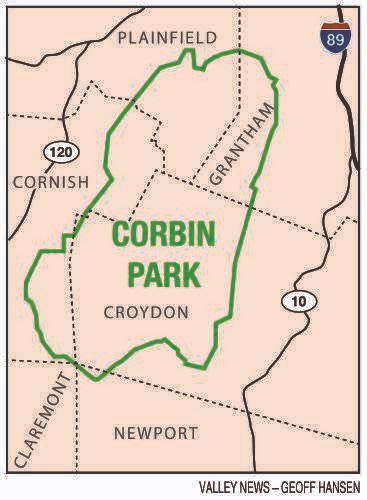

By 1895, the park was estimated to contain 3,000 animals. Bison attracted the most attention and Corbin owned the largest private herd in the United States.58 During the second half of the 19th century, the federal government encouraged hunters to slaughter over 60,000,000 bison as part of a genocidal campaign against the indigenous peoples of the plains regions. Corbin, having witnessed with his own eyes, herds of bison more than 100,000 strong, expressed a desire to save them (but not their human companions) from extinction. He also had dreams of crossing them with cattle to create a superior beef animal from which he would surely profit. Corbin imported bison from Oklahoma, Montana, Wyoming, Texas, and Manitoba. He donated several to zoos and preserves across the country. When Edward VII, Prince of Wales visited the park he was invited to shoot a bison. He ignored the invitation and shot six.59

Image Description: A black & white postcard titled “Buffalo, Corbin’s Park, NH”. Pictured are a group of bison grazing on grasses in front of a deciduous forest. Rocks are strewn about the pasture and the adult bison are accompanied by three calves. End of description.

Image Description: A black & white photograph of bison on a grassy hillside. It’s hard to tell, but there may be as many as twenty bison in the picture. Some are grazing, some are lounging on the ground. Behind them, a few lonely pasture trees are silhouetted above the horizon. Because of how the film was developed, the sky looks a pale yellow and the scene has an almost dreamlike quality. End of description.

Elsewhere, Corbin’s plan for an international port at Montauk was flawed in significant ways, most notably that Fort Pond Bay was too shallow and rocky to facilitate the traffic necessary to compete with New York Harbor. Nevertheless, he proceeded with his scheme by seeking congressional approval for a duty-free international seaport. Repeated lawsuits from the Montauketts had delayed progress but in March of 1896 he began building docks with a new steel pier. Congress balked and voted down his project three times but Corbin would not be thwarted. On June 4, 1896, Corbin was at his park with knowledge that a fourth and likely positive vote would be delivered the following day.60

It was a sunny afternoon and he decided to celebrate by going fishing at Governor’s Pond, below Croydon mountain. With him were his coachman, his nephew, and his son’s tutor. While riding in his horse drawn carriage, he popped open an umbrella to shade himself from the sun. This spooked his horses, who bolted down the road and flung the entire party loose at high speed. Corbin flew eight feet through the air before his skull struck against a stone wall and his head cracked open. Mrs. Corbin and other members of the family witnessed the scenes from the veranda. His carriage driver was reportedly “wound around a tree” and died quickly. Corbin’s nephew had also hit the wall but he and the tutor, who had soared clear over it, survived with injuries. Corbin still clung to life but had multiple compound fractures in his right leg, a four inch gash on his forehead, and another of equal size on the right side of his face which was now bruised and distorted. Immediately, the family sent for Corbin’s doctors, four of them, who arrived by private train in time to watch him expire later that evening.61 62

Fortunately for the ecology of Fort Pond Bay, Corbin’s plans for an international seaport died along with him.63 The value of the estate he left behind is disputed. Some sources estimate that it was worth $5 million but journalists at Newsday report values between $25 million and $40 million, and one source even estimates as much as $85 million.646566 Regardless, adjusted for inflation, his purchasing power in 1896 would have been roughly 35 times what it is today.67

The former maid of Corbin’s wife, Mathilda Nelson, sued his estate that same year. Apparently his mistress, she claimed he was a “frequent visitor” of hers and that he had promised to give her $50,000. Estate lawyers accused her of blackmail and she was vilified in the press. One article dismissed Nelson as a “pretty blonde Swede” and derided the situation saying, “Women of a certain class [...] will proclaim that they had irregular relations with rich men and make claims upon the property which was left.” The estate settled for an undisclosed amount and four years later, Nelson took her own life.68

Corbin’s daughter, Anna Corbin Borrowe, also sued the estate. She had been estranged from the family because they did not approve of her marriage.69 The courts repeatedly ruled against her but she remained undeterred. An article at the time stated, “she appears to rather enjoy the situation” and “there is no indication of her letting up”.70 By the time litigation ended in 1904, the value of the estate had dwindled to $290,000. At least that is what the Corbins reported to tax collectors.71

Laborers at Sunnyside Plantation suffered badly after Corbin’s death. None of his children took interest in the plantation or their father’s half-baked attempt to establish an Italian colony there. An attorney with the US DOJ visited the plantation to look into repeated reports of peonage. She confirmed that peonage was indeed taking place and that only prosecution could put an end to it. Under the influence of local planters, Congressman Benjamin Humphreys disagreed with her assessment and prosecution was stopped in its tracks. The Italian immigrant workers were promised improvement to the plantation’s lackluster irrigation systems but such support never came. As a result, they were beset with malaria and many died. Disillusioned by the terrible conditions and negligence displayed by the Corbin heirs, many survivors simply moved on. Within years, the plantation was defunct, although pockets of Italian-Americans remain in Arkansas today.72

Image Description: A historical marker which tells a story. The text reads: “Italian Immigrants on Sunnyside Plantation. In 1895, Austin Corbin, a New York banker and land developer, working with immigration officials, brought 100 families from north central Italy to grow cotton at Sunnyside, a plantation located between the Mississippi River and Lake Chicot. These Italians struggled against exploitation, prejudice and language barriers, and many died of malaria and other lowland diseases. Many of their descendants are now among the leading citizens of Arkansas and the nation.” End of description.

In 1909, after enduring multiple setbacks at the hands of the courts system, the Montaukett lawsuit finally went to trial. Members of the tribe sought to void deeds to Arthur Benson’s property and return land at Indian Fields and two other sites to the Montaukett people. Now in his 80s, Nathaniel Dominy took the stand. He was the town assessor who Benson hired to acquire the land and did so with empty promises of comfortable homes and acreage. Referring to Maria Pharaoh, a Montaukett person who signed away her land rights under false pretenses, Dominy was asked by lawyers: “Did you tell her that after she moved away, and was given this deed, that she could come back?” Through tears he confirmed, “I told her this. I venture to say… I told every one of them”. Instead of arguing the legitimacy of Benson’s claims, lawyers for the Benson estate argued that the Montauketts had “intermarried with blacks and thus diluted their Indian blood”.73 After a year of deliberation, Judge Abel Blackmar threw out the case, ruling that the Montauketts no longer existed as a tribe, that they were extinct. 75 Montaukett plaintiffs sat in stunned silence. The court’s racist decision left them with no legal standing—a challenge they face to this day.74

Recently, Robert Cooper was elected tribal chief in a disputed vote. He and his cousin, Robert Pharaoh, are determined to see Montaukett tribal rights recognized by the federal government. If successful, they will launch a legal effort to have their lands returned. Experts say that, by modern legal standards, a court could overturn the coercive land deal because of the evidence that false promises were made to the Montaukett people.75 Much of the land at Montauk Point today comprises parkland owned by the county along with private homes.76 The Montaukett people succeeded in protecting Fort Pond Bay from excavation, but they suffered great harm at the hands of voracious capitalists like Arthur Benson and Austin Corbin.

Image Description: A color photograph of coastal lands at Indian Fields. It is a beautiful scene in which shimmering waters enter into some grassy marshlands. The marshes are shielding tidal pools from waves in the bay. The sky is light blue and the vegetation is a mixture of greens and yellowed browns. Flowering shrubs pop up in the immediate foreground with their little whitish flowers. Small trees and bushes make up the background. End of description.

Like his other prized possessions, Corbin named his son after himself. Following his father’s death, the younger Austin Corbin took control of the park and for a few decades, he presided over what some called the park’s “golden years”.77 He entertained powerful, famous guests such as Teddy Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, Woodrow Wilson, and Joe DiMaggio. Though it is often reported, there is no conclusive evidence that Rudyard Kipling ever visited Corbin's New Hampshire estate.

The prominent naturalist Ernest Baynes, a resident of Meriden, New Hampshire, became enamored with the animals in Corbin’s Park. Having been born to English parents in Calcutta, India, he grew into a man likened to Doctor Doolittle for his love of wildlife. Baynes led a crusade to save bison from extinction which eventuated in the foundation of the American Bison Society. He wrote a book about his two favorite bison from Corbin’s herd, which he named “Tomahawk” and “War Whoop”. He drove the two bison at sportsmen shows, hitched to a wagon. He claimed they were the only team of bison in the world. 78

Image Description: A black & white postcard, featuring Ernest Baynes and his famous team of bison. The two bison are hitched to a wagon, atop which sits Baynes. They are positioned in front of a grassy, hillside pasture. The wagon has big wheels with wooden spokes. Baynes is wearing a dark sportcoat and a lighter colored hat. In his hand is a long crop, presumably for walloping the bison. End of description.

After being deforested, overgrazed, and then abandoned, many New England pastures were taken over by white pine trees. These stands were referred to as second-growth.79 In 1915, second-growth white pine timber from Corbin’s park was cut and then drawn to True’s farm, just over the town line in Lebanon. There, the logs were rolled into the Connecticut River as part of the river’s last log drive. Over 200 men took part in the incredibly dangerous and often romanticized task of guiding entire forests worth of trees down the river. Historically, loggers did so by standing atop the moving barge of logs as it traveled downstream. Many drowned after falling in and getting stuck under the logs. Makeshift gravesites can still be found along the river today. Log runs in wintertime meant that when logs became jammed by ice, dynamite was used to dislodge them. By the time the last log drive reached North Stratford, New Hampshire, there was already 65 million feet of timber in the water.80

For a relatively short period of time, the park was open to visitors. One resident recalls retrieving the gate key from its hook in the Cornish Flat general store. There were originally nine gates, each with a keeper’s lodge including four public or pass gates. It is worth noting that formal and informal segregation still made the park inaccessible to most of the world's population. Over time, the park became less accessible even to white people.

In the late 1930s, the bison herd had been allowed to dwindle due to costs associated with feeding and management. The herd developed Bang’s disease and the last bison was shot just a few years later.81 The Corbin fortune continued to ebb away and when the younger Corbin died in 1938, he did so “penniless”, according to one source.82 That same year, the region was rocked by a historic hurricane. 160 mile per hour winds felled so many trees that the lumber market immediately plummeted.83 Evidence is still visible in our forests today. The storm severely damaged the park fence and animals were able to leave freely, much to the ire of local farmers.

In 1941, large herds of elk were seen migrating back and forth through the towns of Washington, Goshen, Unity, Lempster, and Marlow.84 Elk are much larger than deer. A mature elk can weigh between 600 and 1000 pounds. One of their indigenous names, wapiti, is a Shawnee word meaning “white rump”. Before English settlement, they had roamed the region in great numbers. Settlers killed them off in what was described as an “exterminating butchery”.85 Those that escaped from Corbin Park simply lived as their predecessors had, browsing for edible vegetation. However, not all of the elk from Corbin’s park were escapees.

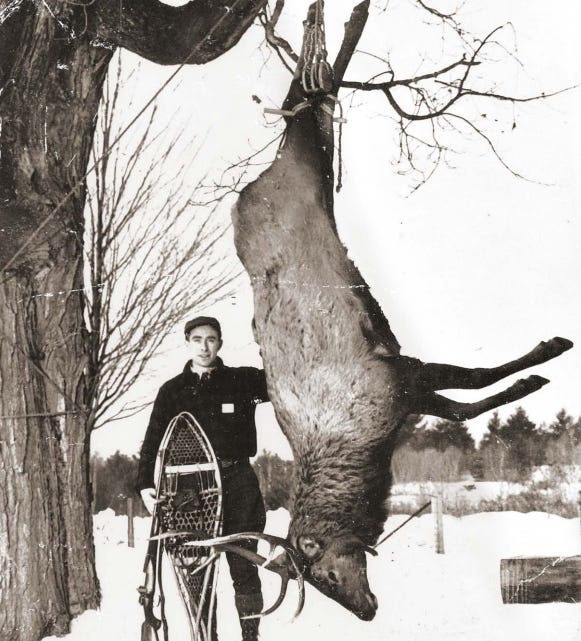

Starting back in 1903, Corbin’s son had entered into a relationship with the State of New Hampshire in which he provided elk for repopulation outside the park. The Andover Fish & Game club released them in the vicinity of Ragged Mountain. More were released in the Pillsbury Reservation of Washington and Goshen.86 Local planters complained that the animals fed off their hay and other foods in their yards. Some elk were shot by angry farmers or poachers. In 1915, the state passed a law requiring payment for game damage. The elk persisted for decades and eventually, locals raised such a fuss that New Hampshire instituted its first and only elk hunting season in 1941. Two hundred hunters, who paid $5 for a license, shot and killed 46 elk over two days.87

Image Description: A black & white photograph of a man posing with a dead elk hanging upside down from a sugar maple tree. The man is holding a pair of snowshoes, an indigenous winter technology. The elk is enormous and the man looks slight in comparison. The elk’s antlers, which are nearly touching the man, are sharp and formidable. End of description.

In 1944, the Corbins finally washed their hands of the park. Controlling interest of the Blue Mountain Forest Association was transferred by the family to a group headed by Mortimer Proctor, Republican candidate for governor of Vermont.88 Proctor’s great grandfather, Redfield Proctor, founded the Vermont Marble Co. and was elected governor of Vermont in 1878. The Proctor family proceeded to run the state with few interruptions for the next 80 years. When Mortimer was elected in 1944, he completed the fourth generation of Proctor governors. When they weren’t in office, the Proctors handpicked candidates from the allied worlds of industry, utilities, railroads, and insurance.89

Boar that escaped and lived outside the park became such a nuisance that in 1949, the New Hampshire legislature passed another special law holding BMFA responsible for damage caused by escaped pigs. In the 1950s, local farmers sued BMFA for damages, which the park fought unsuccessfully all the way to the state Supreme Court.90 Local hunter Sonny Martin recalls shooting a large escaped boar from his tree stand in a moment of serendipity.91 BMFA alleges that other hunters took a more proactive approach, cutting holes in the fence and sprinkling corn kernels to lure pigs out into the open.92 In 1950 and 1951, 30 tons of whole kernel corn “literally poured from the skies” onto the boars’ feeding grounds in an airlift called “Operation Wild Hog.”93

In 1953, more animals escaped when the fence was opened in multiple locations to fight a forest fire within the park. On the summer solstice of that year, a bolt of lightning set the woods ablaze. The fire burned for seven days before firefighters could find it and respond.94 Naturally occurring fires are an integral part of our forest ecosystems. In addition to selective burning by indigenous peoples, historically, forest fires contributed to the mosaic landscape of pre-colonial New England. Fires create forests in varying stages of succession, which is crucial for the overall health of the ecosystem.95 Today, most fires are sought out and extinguished to prevent damage to permanent settler establishments.

While stationed in a lookout tower on Croydon Mountain, Bud Gross received several reports of smoke coming from the park. Though they looked, neither he, nor the other fire officers were able to see any smoke. On the seventh day, a crew set out for Grantham Mountain to find the source of the smoke. They found it atop the mountain, so thick that they couldn’t see through it. By day eight, teams of firefighters worked without roads, trails, or water, hacking fire-breaks through the forest. This entails clear-cutting a wide swath through the woods and disturbing the earth so thoroughly that the fire cannot sustain itself. A crew of ten firefighters nearly died when they were trapped by flames on all sides. On the thirteenth day, 359 soldiers arrived from Fort Devens in Massachusetts. They were soon followed by 200 airmen from Grenier Field in Manchester. Their ten-wheeled army trucks destroyed the forest floor. Several times the fire sprang back to life before being put out for good. Once the fire was finally extinguished, all the plants atop Grantham Mountain had burned away. The thin layer of soil that was once forest floor, now lay exposed. Without roots to hold it in place, the soil soon eroded. This is why today, the white granite peak of Grantham Mountain remains bare of vegetation.96

Farmers continued to complain about elk outside the park. In 1955, the state announced: “The director of fish and game is hereby directed to reduce the elk herd in the state to a population that will no longer present a potential threat to agricultural interests. The reduction of this herd shall be started at once and carried to completion without unnecessary delay.” The act also contained a provision that financial proceeds from the hunt go toward establishing an elk herd in the northern regions of the state, though nothing ever came of this proposal. In March of 1955, conservation officers and an irate farmer killed sixteen elk in an attempt to exterminate them locally. It is believed that farmers and poachers killed the few remaining elk.97

After changing hands, Blue Mountain Forest Association (BMFA) withdrew further and further from the public eye. They made news only a few times in the second half of the 20th century. In the 1970s, the towns of Croydon, Cornish, and Plainfield refused to grant the park a property-tax abatement under the current use program. The towns argued that the park’s primary use as a hunting preserve did not entitle BMFA to the reduced assessments given for agricultural and forest land. This time, BMFA sued and won. Plainfield selectman Steve Taylor said of the dispute, "We felt if it had a fence around it and it wasn't accessible to the public, there really wasn't any public benefit. But the court said no." Some argue that keeping the land from being developed is enough of a public benefit. In 1998, the park’s current-use tax break amounted to around $200,000.98

Image Description: A color photograph of one of the park gates. It is made of chain link and backed by very sturdy looking metal. The fence is only about 8 feet tall in this section. Tire tracks and boot prints mark the snow going into the park. A dirt road disappears off into the woods. End of description.

Besides the odd escaped boar being hit by cars, the park kept a low profile, receiving little to no public attention until 2004. On January 3rd of that year, a man named Steve Laro shot and killed Robert Proulx, a member of his hunting party99. Proulx owned a taxidermy shop in Manchester, NH where he had sold Laro the gun that eventually took his life.100 According to the Union Leader, Laro is a “former military police officer, a decorated marksman, an FBI-certified firearms instructor, and an experienced hunter”.101 In his late 40s at the time, Laro said he believed that he was shooting at a boar when he shot Proulx from 72 yards away102. He was charged with and later acquitted of negligent homicide and felonious use of a firearm.103

After her husband’s death and following Laro’s acquittal, Susan Proulx asked the state to revoke Laro’s hunting license, stating: “He’s a danger to other hunters. You identify your target before you shoot, period. When you’ve taken a person’s life then you shouldn’t be allowed to have the privilege of hunting again.” County Attorney Marc Hathaway echoed her sentiments, saying, “[Laro] knows the importance—as does every hunter—of being able to identify his target. He was not ready to hunt. His scope was not adjusted.”104 Laro was hunting with his scope set on a magnification of five, in foggy and rainy conditions.105 Conservation Sargent Brian Suttmeier, supervisor of the initial search and investigation, said of the incident, “I don’t believe that with all the training that he aspires to—and because he killed somebody—that he is competent.”106 The state agreed and Laro’s license was revoked. Reflecting on his testimony, Grafton County Commissioner Sharon Guaraldi said, “I didn’t hear anything in Mr. Laro’s testimony indicating that [he] learned [his] lesson.” When asked what advice, based on his experience, he would give to other hunters, Laro said repeatedly, “Don’t ever say it’s not going to happen to you.”107

Of course, for hunters who take the necessary precautions, “it” does not happen at all, much less “to” them. A glance into Laro’s past reveals a pattern of deplorable behavior. According to journalists at NHPR, during his career as a police officer he consistently displayed what was described as “professional dishonesty”. In his first job as a policeman, he received so many letters of complaint that his former chief said his personnel file was three inches thick, full of accusations of misconduct and abuse, both verbal and physical in nature. In some instances, he choked people who questioned his demeanor. His behavior was so out of control that the chief sent him to see a psychologist who concluded that Laro “should not be entrusted with a gun and a badge,” adding that “he should be referred to counseling”. Despite his record, he received another gun and badge when he was hired by the Franklin, Massachusetts Police Department. There, he continued with his already well-documented behaviors. This reflects rather poorly on the ethical standards required for police duty. His antics became so infamous that a lawyer for the state told the Franklin chief, “if you had a homicide tonight in Franklin, I would instruct you that Sargent Laro not be involved [in] any capacity.”108

The fight to revoke Laro’s license is part of a larger licensure debate surrounding BMFA. Members who come to hunt elk and boar are not required to purchase hunting licenses. Despite repeated attempts by legislators to require licensure, BMFA remains protected by the New Hampshire constitution and the “special law” that governs the park. This refers to an 1895 legislative act that established the park as a private hunting preserve.109 BMFA argues that since the elk and boar are descendants of animals that Corbin introduced to the park for hunting, they constitute private property and are therefore not part of the “public commons” like deer, bear, and wild turkeys. Fish and Game Director Glenn Normandeau rhetorically asked the Fish and Game Committee, “Are you going to impose this on a farmer, also?” His question followed a discussion that equated the legal status of Corbin’s elk and boar with livestock.110 The obvious answer is no, because Corbin Park is clearly not a farm. Frustratingly, the obvious answer and the legal outcome often differ.

Image Description: A color photograph of a no trespassing sign. It reads: “NO TRESPASSING. The enclosed park fence and signs are protected by a special law of this state and any person trespassing herein or in any way violating that law will be prosecuted. If you have lost an animal or have a legitimate need to enter the park, call the superintendent at 6 0 3, 8 6 3, some illegible number, 2 5 0. Do not trespass. The Blue Mountain Forest Association. End of description.

Relatively little is known about how BMFA currently operates. There are roughly 30 members and some of their names appear on tax documents. After all, the park is a non-profit. One member is the CEO of a plastics company, another owns a company that built a stealth boat to be sold to the US military, another member owns a major gun manufacturing company, and another is a member of the Von Trapp Family Singers. To gain membership, one must buy the shares of a former member. This way, numbers stay consistent and members control who can enter. Specific figures are unconfirmed but membership fees are rumored to be around $25,000 annually. Members shoot between 200 and 600 boar each year, and between 40 and 120 elk. From the tax forms, one can see that the park makes money butchering meat for members and guests, but most of their income comes from membership dues.111 BMFA spends over $300,000 a year on feed alone.112

The late Representative Renny Cushing argued that “Every other hunter in the state, who doesn’t have access to Blue Mountain, ends up subsidizing the hunting in that reserve.” Within a decade, Cushing proposed a total of four bills that would give the Fish and Game Department authority to require “any person wishing to take exotic game including wild boar or elk from a hunting preserve” to buy a special “safari hunting license.” Cushing’s first three bills all died in committee. To his fourth, he added an amendment proposing that $25 from the proposed license fee be put into a “feral swine mitigation fund” in the event of future escapees.113

Regarding Cushing’s bill, BMFA President Peter Crowell admitted that boar from the park do escape now and then, but he blamed it on locals, claiming that they cut the fence to lure the pigs out. He says BMFA has installed cameras in trouble areas and that they run regular patrols to ensure the integrity of their fence.114 From firsthand experience, the men in trucks and on snowmobiles who years ago returned my inquisitive gaze through the fence, were indeed intimidating, not least because of their visible weaponry.

Crowell dismissed a major concern that often accompanies boar: that they can pose a threat to agricultural interests, people, and even entire ecosystems.115 This is a complicated issue. Many authoritative sources refer to boar as an invasive species, but a more accurate view is that they are displaced. According to the National Wildlife Federation, the feral hogs running rampant across many parts of the United States are descendants of Eurasian boar, escaped domestic pigs, or hybrids of the two. They were brought by European colonizers, firstly, the Spanish. The problem was exacerbated in the 1980s when many settlers captured boar and brought them to new areas to let them become established for the purposes of hunting.116 This still happens today.117 Boar are introduced to unstable environments with conditions that prevent the local ecosystem from finding equilibrium.118 Nevertheless, boar frequently disrupt settler agriculture and a pack of them even killed a person in Texas.119

Crowell said that the boar in the park are Eurasian boars, imported from Germany in the 1800s and thus, not the problem that other species can be. He said that “they do not breed the way a feral hog would breed,” and that they produce fewer litters with fewer babies than other species. Eurasian boar however are specifically listed as a problem species by many states. New York State, for example, says the breed is a “highly adaptable, destructive, non-native, invasive species that can damage habitat and crops and threaten native animals and domestic livestock.”120 It appears that Crowell’s assertions are incorrect. Additionally, assessments of the problems posed by wild boar and other so-called invasives often place blame on plants and animals rather than acknowledge the multilayered roles that settler colonialism and racial capitalism play in ecological degradation.

Like his others, Cushing’s fourth bill never made it out of committee.

Image Description: A color photograph of a beaver pond. Water shimmers in the foreground while grassy marshes and an array of standing dead trees make up the middle ground. They are backed by a steep, broad hillside of gray, leafless deciduous trees. Along the edge of the water and atop the far ridge are two lines of spruce and hemlock, their needles dark green in appearance. This photo is from Chase Pond, just outside the fence. End of description.

Throughout its history, regardless of whose name is on the deed, members of the Blue Mountain Forest Association have displayed a pattern of behaviors ranging from unethical to downright despicable. Austin Corbin began the trend by taking advantage of everyone and everything in his sight. Mortimer Proctor and company bought the park with wealth generated by his family running the state of Vermont for their own gain. Steve Laro, though perhaps not a member himself, refused accountability for his role in Robert Proulx’s death. BMFA’s current owners pay $25,000 every year for membership alone, but use legal acrobatics to evade the small fees assessed to other hunters. The entire history speaks to an aspect of Corbin Park’s true nature: it is a place where powerful white men come to act with impunity.

In essence, Corbin Park is little more than a canned-hunting operation masquerading as a wildlife conservation project. The land within the fence is stunningly beautiful and I am glad that it has not been turned into a strip mall, but the park should never have been allowed to exist. However, since it does exist, it cannot simply be disbanded. There are thousands of boar within the fence, visible from satellite imagery, whose populations far exceed the carrying capacity of the land there. They are sustained by feed and their only predators are 30 transient millionaires and their guests. Ironically, the park fence is now preventing an ecological disaster, one that Corbin set in motion over 100 years ago. In that time, storms have grown more intense, only increasing the likelihood of future damage to the fence.

What is to be done then with Corbin’s monstrosity?

For years, I’ve dreamt of what Corbin’s park could be. There is an abundance of potential waiting to be redistributed. This predicament brings unique opportunities. I believe that the park should be returned to the commons.121 With indigenous leadership, foresters and land-workers could devise an intentional, strategic approach to land stewardship, divorced from the profit motive. I envision a future in which public hunting programs operate out of the park, having been renamed for a less ignominious figure. People could register and learn to hunt wild boar, elk, and deer, while accompanied by experienced guides. People of all ages could take courses on how to clean and butcher animals and learn how to craft other homemade products. Perhaps it could even be a place to reintroduce larger predators like the legendary catamount or wolf. A single community pig roast would provide significantly more public utility than the park currently does. Just imagine an ongoing series of barbecues and community events.

I can also see an opposing timeline, one in which Corbin Park becomes an even more militarized compound to keep out undesirables—the rest of us. As the climate crisis worsens, we desperately need visions for a collaborative, collective future. Thankfully, such visions already exist, but entities like BMFA are antithetical to them.122

The end.

Thank you for reading.

Please add your name to my email list to be notified when I publish new natural history writing.

BROOKS, DAVID. “Legal Status of Game Preserve Complicates Question of Whether Its Users Need Hunting Licenses.” Concord Monitor, Concord Monitor, 14 Jan. 2020, www.concordmonitor.com/corbin-park-bluemountain-nh-hunting-preserve-game-31987801. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Evans-Brown, Sam. “Millionaires’ Hunt Club.” Outside/In, 29 Dec. 2016, outsideinradio.org/shows/ep27. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Evans-Brown, Sam. “Millionaires’ Hunt Club.” Outside/In, 29 Dec. 2016, outsideinradio.org/shows/ep27. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Cronon, William. Changes in the Land : Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. 1983. New York, Hill And Wang, 2003.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Schaer, Sidney. “Riding the LIRR Together.” MORE LIRR/AUSTIN CORBIN INFO from NEWSDAY, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/NewsdayCorbinArticle2.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Sullivan, David. “The Rise and Fall of Coney Island’s Manhattan Beach.” Heart of Coney Island, www.heartofconeyisland.com/manhattan-beach-coney-island-history.html. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1890/900200-debs-austincorbin.pdf

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Sullivan, David. “The Rise and Fall of Coney Island’s Manhattan Beach.” Heart of Coney Island, www.heartofconeyisland.com/manhattan-beach-coney-island-history.html. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Sullivan, David. “The Rise and Fall of Coney Island’s Manhattan Beach.” Heart of Coney Island, www.heartofconeyisland.com/manhattan-beach-coney-island-history.html. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Sullivan, David. “The Rise and Fall of Coney Island’s Manhattan Beach.” Heart of Coney Island, www.heartofconeyisland.com/manhattan-beach-coney-island-history.html. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Schaer, Sidney. “Riding the LIRR Together.” MORE LIRR/AUSTIN CORBIN INFO from NEWSDAY, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/NewsdayCorbinArticle2.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Wikipedia. “Sunnyside Plantation.” Sunnyside Plantation, Wikipedia, 5 Oct. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunnyside_Plantation. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Metrailer, Jamie. “Encyclopedia of Arkansas.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/sunnyside-plantation-4455/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Wikipedia. “Sunnyside Plantation.” Sunnyside Plantation, Wikipedia, 5 Oct. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunnyside_Plantation. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Metrailer, Jamie. “Encyclopedia of Arkansas.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/sunnyside-plantation-4455/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Dennis, Jeremy. “Indian Fields.” On This Site, www.jeremynative.com/onthissite/listing/indian-fields/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Throwback Thursday - One Final Blow.” Montauk Library, 12 Oct. 2022, montauklibrary.org/throwback-thursday-one-final-blow/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Schaer, Sidney. “Riding the LIRR Together.” MORE LIRR/AUSTIN CORBIN INFO from NEWSDAY, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/NewsdayCorbinArticle2.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Wessels, Tom, et al. Reading the Forested Landscape : A Natural History of New England. New York The Countryman Press, 1999.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Gross, Rita, et al. Corbin Park PDF. www.meyette.us/CorbinPark.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Evans-Brown, Sam. “Millionaires’ Hunt Club.” Outside/In, 29 Dec. 2016, outsideinradio.org/shows/ep27. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Wessels, Tom, et al. Reading the Forested Landscape : A Natural History of New England. New York The Countryman Press, 1999.

Cronon, William. Changes in the Land : Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. 1983. New York, Hill And Wang, 2003.

Gross, Rita, et al. Corbin Park PDF. www.meyette.us/CorbinPark.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Meyette, Brian. Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinPark.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Meyette, Brian. Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinPark.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Miller, Tom. “Daytonian in Manhattan: The 1888 Corbin Building -- Broadway and John Street.” Daytonian in Manhattan, 1 May 2012, daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2012/05/1888-corbin-building-broadway-and-john.html. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Schaer, Sidney. “Riding the LIRR Together.” MORE LIRR/AUSTIN CORBIN INFO from NEWSDAY, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/NewsdayCorbinArticle2.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“The Enterprise 1904-01-02.” Internet Archive, The Enterprise, 2 Jan. 1904, archive.org/stream/cssf_000443/cssf_000443_access_djvu.txt. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Value of 1896 Dollars Today | Inflation Calculator.” Www.in2013dollars.com, 10 Nov. 2022, www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1896#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20dollar%20has%20lost%2097%25%20its%20value%20since%201896&text=%24100%20in%201896%20is%20equivalent. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Miller, Tom. “Daytonian in Manhattan: The 1888 Corbin Building -- Broadway and John Street.” Daytonian in Manhattan, 1 May 2012, daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2012/05/1888-corbin-building-broadway-and-john.html. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

NEHS. “Austin Corbin ROBBER BARON.” New England Historical Society, 2022, rihs.us/2020/05/20/wednesday-may-20-2020-austin-corbin-robber-baron/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Wikipedia. “Sunnyside Plantation.” Sunnyside Plantation, Wikipedia, 5 Oct. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunnyside_Plantation. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Throwback Thursday - One Final Blow.” Montauk Library, 12 Oct. 2022, montauklibrary.org/throwback-thursday-one-final-blow/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

“Lost Indian Lands: Tribes Fight for Areas Taken in Questionable Deals.” NEWSDAY ARTICLE about CORBIN and HIS DEALS, Brian Meyette, 17 June 2010, www.meyette.us/NewsdayArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Dennis, Jeremy. “Indian Fields.” On This Site, www.jeremynative.com/onthissite/listing/indian-fields/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Meyette, Brian. Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinPark.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Kronenwetter, Mary. Kronenwetter Article on Corbin Park. Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/KronenwetterArticle.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Wessels, Tom, et al. Reading the Forested Landscape : A Natural History of New England. New York The Countryman Press, 1999.

Zea, Howard, and Nancy Norwalk. Choice White Pines and Good Land. Portsmouth, NH, Peter E. Randall, 1991.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Evans-Brown, Sam. “Millionaires’ Hunt Club.” Outside/In, 29 Dec. 2016, outsideinradio.org/shows/ep27. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Wessels, Tom, et al. Reading the Forested Landscape : A Natural History of New England. New York The Countryman Press, 1999.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Shea, Susan. “Elk Once Roamed the Northeast, until an “Exterminating Butchery.”” Valley News, Valley News, 14 Jan. 2019, www.vnews.com/Outside-Story-Did-you-know-there-used-to-be-elk-in-New-England-22725208. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Vachon, Jane. The Great New Hampshire Elk Hunt of 1941. Nov. 2013, www.wildlife.state.nh.us/pubs/documents/samples/wj-elk-hunt.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

NEHS. “How Vermont Republicans Rigged Elections for a Century.” New England Historical Society, 4 June 2013, www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/vermont-republicans-rigged-elections-for-century/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Billin, Dan. Private Game Preserve Has Storied History. Valley News, 28 Jan. 2004, www.meyette.us/DanBillinCorbinParkArticle.htm. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Evans-Brown, Sam. “Millionaires’ Hunt Club.” Outside/In, 29 Dec. 2016, outsideinradio.org/shows/ep27. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

BROOKS, DAVID. “Legal Status of Game Preserve Complicates Question of Whether Its Users Need Hunting Licenses.” Concord Monitor, Concord Monitor, 14 Jan. 2020, www.concordmonitor.com/corbin-park-bluemountain-nh-hunting-preserve-game-31987801. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Chace, Cory. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Corbin Park Timeline, Brian Meyette, www.meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022. The timeline references various articles in the Argus newspaper from 1835 through 1994. Entries compiled by Cory Chace.

Grantham Historical Society. Corbin Park Fire of 1953. zh-cn.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=369211894672470&set=pcb.369212801339046.

Cronon, William. Changes in the Land : Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. 1983. New York, Hill And Wang, 2003.

Grantham Historical Society. Corbin Park Fire of 1953. zh-cn.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=369211894672470&set=pcb.369212801339046.

Vachon, Jane. The Great New Hampshire Elk Hunt of 1941. Nov. 2013, www.wildlife.state.nh.us/pubs/documents/samples/wj-elk-hunt.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Billin, Dan. Private Game Preserve Has Storied History. Valley News, 28 Jan. 2004, www.meyette.us/DanBillinCorbinParkArticle.htm. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Associated Press. “Key Charge Dropped in Hunting Fatality - the Boston Globe.” Archive.boston.com, Boston Globe, 12 Dec. 2014, archive.boston.com/news/local/articles/2004/12/12/key_charge_dropped_in_hunting_fatality/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Wang, Beverley. “Widow Wants Hunter’s License Revoked.” Portsmouth Herald, 14 Apr. 2005, www.seacoastonline.com/story/news/2005/04/14/widow-wants-hunter-s-license/51215268007/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Tracy, Paula. Dead Hunter’s Wife Says Shooter Should Never Be Allowed to Hunt Again. Union Leader, thefiringline.com/forums/showthread.php?t=163207. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Wang, Beverley. “Widow Wants Hunter’s License Revoked.” Portsmouth Herald, 14 Apr. 2005, www.seacoastonline.com/story/news/2005/04/14/widow-wants-hunter-s-license/51215268007/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Associated Press. “Key Charge Dropped in Hunting Fatality - the Boston Globe.” Archive.boston.com, Boston Globe, 12 Dec. 2014, archive.boston.com/news/local/articles/2004/12/12/key_charge_dropped_in_hunting_fatality/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Associated Press. “Key Charge Dropped in Hunting Fatality - the Boston Globe.” Archive.boston.com, Boston Globe, 12 Dec. 2014, archive.boston.com/news/local/articles/2004/12/12/key_charge_dropped_in_hunting_fatality/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Tracy, Paula. Dead Hunter’s Wife Says Shooter Should Never Be Allowed to Hunt Again. Union Leader, thefiringline.com/forums/showthread.php?t=163207. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Wang, Beverley. “Widow Wants Hunter’s License Revoked.” Portsmouth Herald, 14 Apr. 2005, www.seacoastonline.com/story/news/2005/04/14/widow-wants-hunter-s-license/51215268007/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.